STILL LIFE

STILL LIFE

March 26, 2020

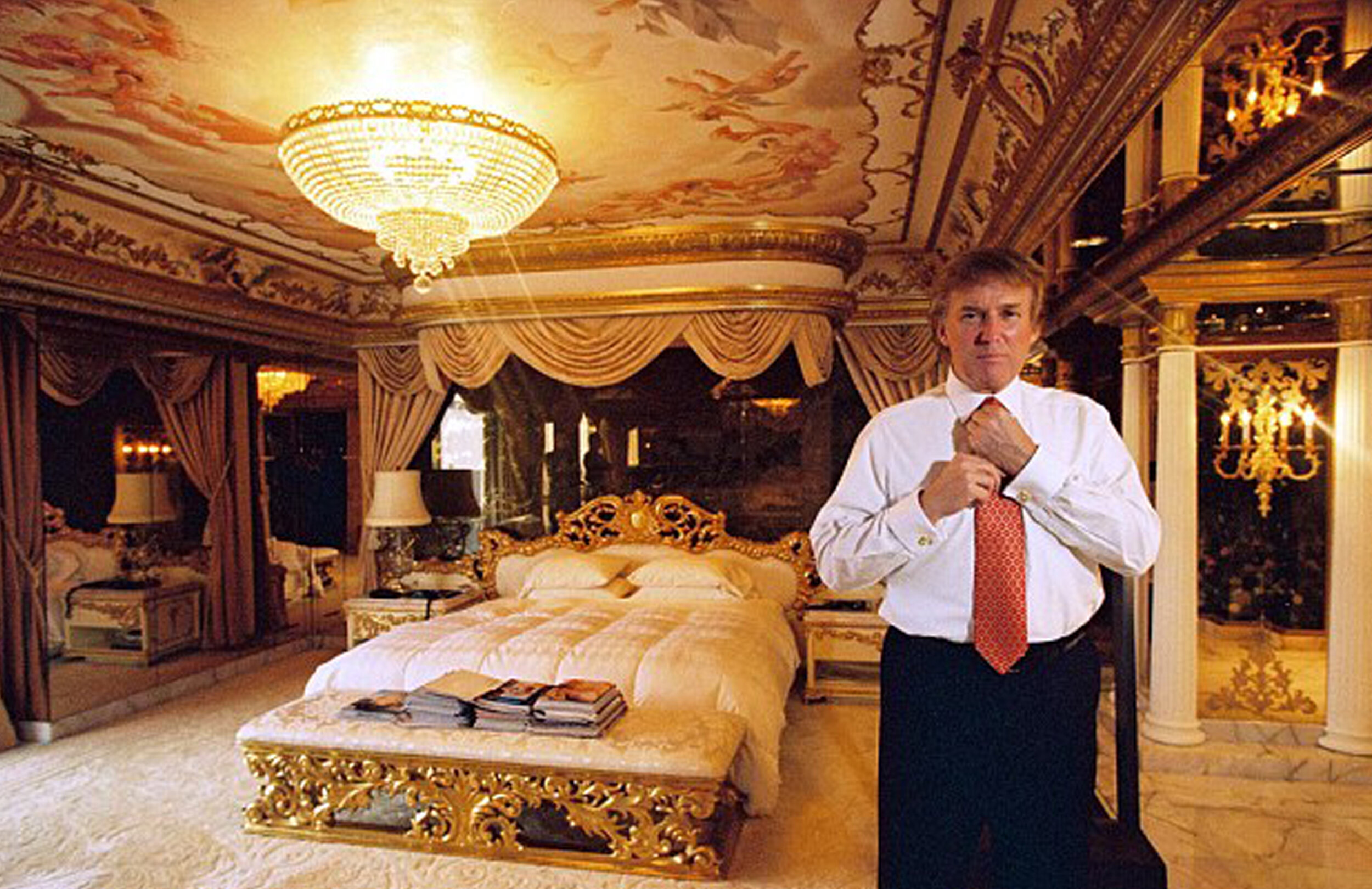

President Donald J. Trump wants America "opened up and just raring to go by Easter". There’s clearly an urgency in his words, not because he is troubled by how many people will die during this pandemic, and not because he is mindful of what will become of the American economy. He wants a Happy Easter so that his polling numbers will shoot for the sky - because he lives in an anecdotal world, a world of one, a world of him alone. His words illustrate the warped reality in which he lives. And we are observing his transition from that of an undiagnosed sociopath to that of an undiagnosed psychopath. If we follow him, people will die, institutions will collapse, and his godhead will dissolve into tragedy for those who walk through his valley of the shadow of death - for he alone can’t fix, really, anything. For he is a parasite with no empathy, and he has no business running our country.

We need to stop listening to this man and his acolytes, and start thinking for ourselves. If we thought more like Einstein and less like servants of a god, we would be less like sheep. We could lead lives of deep humility and deep satisfaction. Here is an excerpt from a book that can make sheltering at home a worthwhile adventure, a time that enables you to step outside of the verities that form your beliefs and guide your life.

I surely didn’t write this particular story; it is inarguably beyond my ken. The book from which it is excerpted is entitled: “Einstein’s Dreams”, written by Alan Lightman, an MIT physicist who looks at the intersection between science, philosophy, and spirituality, with a transcendent brilliance. Lightman wrote this book as a series of thought experiments that Einstein could have imagined while living in Zurich during his “Annus Mirabilis” - his Miracle Year of 1905. Einstein published a paper on Special Relativity, and three others for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1922. I have included this excerpt from “Einstein’s Dream” to remind you that we don’t live to work; we work to live – and to make you want to buy Lightman’s book, if you haven’t already read it.

“MAY 29, 1905

A man or a woman suddenly thrust into this world would have to dodge houses and buildings. For all is in motion, houses and apartments mounted on wheels, go careening through Bahnhofplatz and race through the narrows of Marketgasse, their occupants shouting from second-floor windows. The Post Bureau doesn’t remain on Postgasse, but flies through the city on rails, like a train. Nor does the Bundeshaus sit quietly on Bundgasse. Everywhere the air whines and roars with the sound of motors and locomotion. When a person comes out of his front door at sunrise, he hits the ground running, catches up with his office building, hurries up and down flights of stairs, works a desk propelled in circles, gallops home at the end of the day. No one is still.

Why such a fixation on speed? Because in this world, time passes more slowly for people in motion. Thus, everyone travels at high velocity to gain time.

The speed effect was not noticed until the invention of the internal combustion engine and the beginnings of rapid transportation. On September 8th, 1889, Mr. Randolph Whig of Surrey took his mother-in-law to London at high speed in his new motor car. To his delight, he arrived in half the expected time, a conversation having scarcely begun, and decided to look into the phenomenon. After his researches were published, no one went slowly again.

Since time is money, financial considerations alone dictate that each brokerage house, each manufacturing plant, each grocer’s shop constantly travel as rapidly as possible to achieve advantage over their competitors. Such buildings are fitted with giant engines of propulsion and are never at rest. Their motors and crankshafts roar far more loudly than the equipment and people inside them.

Likewise, houses are sold not just on their size and design, but also on speed. For the faster a house travels, the more slowly the clocks tick inside and the more time available to its occupants. Depending on speed, a person in a fast house could gain several minutes on his neighbors in a single day. This obsession with speed carries through the night, when valuable time could be lost, or gained, while asleep. At night, the streets are ablaze with lights, so that passing houses might avoid collisions, which are always fatal. At night, people dream of speed, of youth, of opportunity.

In this world of great speed, one fact has been only slowly appreciated. By logical tautology, the motional effect is all relative. Because, when two people pass on the street, each perceives the other in motion, just as a man in a train perceives the trees to fly by his window. Consequently, when two people pass on the street, each sees the other’s time flow more slowly. Each sees the other gaining time. This reciprocity is maddening. More maddening still, the faster one travels past a neighbor, the faster the neighbor appears to be traveling.

Frustrated and despondent, some people have stopped looking out their windows. With the shades drawn, they never know how fast they are moving, how fast their neighbors and competitors are moving. They rise in the morning, take baths, eat plaited bread and ham, work at their desks, listen to music, talk to their children, lead lives of satisfaction.

Some argue that only the giant clock tower on Kramgasse keeps the true time, that it alone is at rest. Others point out that even the giant clock is in motion when viewed from the river Aare, or from a cloud.”

Image: The Human Condition, René Magritte, 1933